1.27.2023

Negative Space (Why It's Such a Big Deal)

1.24.2023

Facial Features: Cross-Contour Mouth Sketch

by Lisa Larrabee

If you want to improve your drawing and painting, take time to focus on your subject from an academic perspective. Although it is essential to play and experiment, it is also important to dedicate time for disciplined study to learn more about your subject. In this example, I focused on the mouth. However, this type of practice will help you better understand the form of any subject.

I worked from a photograph for this study. I added cross-contour lines to better understand the dimensional form of the mouth. Cross-contour lines are lines that follow the surface of the form. (In contrast, contour lines follow the edge or boundary of the form like an outline).

1.17.2023

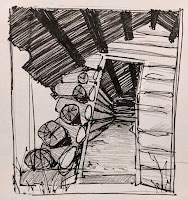

Expressive Mark Making

by Lisa Larrabee

Not everything we make needs to become something. I cannot stress enough the importance of experimentation and play without an end result in mind.

This is a demo where I modeled a variety of different types of mark-making using graphite and charcoal.