by Lisa Larrabee

Value does all the work, but color gets all the credit. That phrase gets thrown around a lot, but what does that even mean?

We love color! Colors can be subtle or dazzling. Colors are powerful and can be used to get our attention or to communicate feelings. However, value relationships are often the foundation of a drawing or painting. Values can be essential to providing structure and to creating the illusion of light, form and depth.

Organize Colors by Value

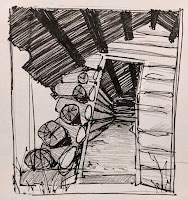

If you want to experiment and take some risks with color, it can help to begin by first considering your values. In the example below, I began with a black and white photo reference that had a nice range of light, medium and dark values. I selected colors fairly randomly based on what I thought looked interesting while making sure I had different values. I then sampled the colors on my gray toned paper in order of dark to light.

I have been inspired recently by the drawings of Viktoria Maliar and her bold mark-making and color choices. It reminded me of exercises I did when studying the mark-making of Vincent Van Gogh's portraits back in college. I approached this study similar to others I have done when experimenting with my color choices. I focused on placing values where they belonged regardless of whether it made sense for the local color of the subject and with zero regard for lighting color or temperature.